By Julia Lyon | The Salt Lake Tribune

From New York to Utah, refugees who can’t find a job, don’t have enough food or feel abandoned by caseworkers look for help -- in Thailand.

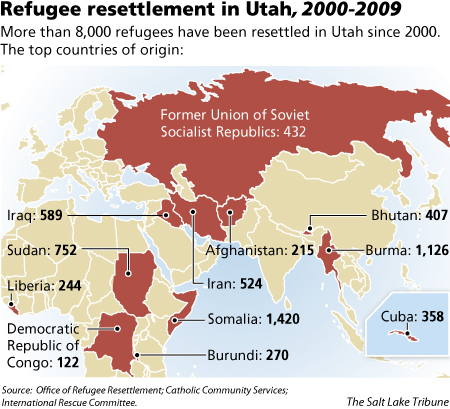

And eight thousand miles away, at all hours, Blooming Night Zan’s phone rings. Refugees know her as a spitfire advocate for the Burmese, both those who have fled to camps in Thailand and those still living under military rule in their home country.

But over the past two years, as large numbers of Burmese refugees have been resettled to the U.S., a new cause has demanded her time: the unexpected plight of those lucky enough to get to America.

The frustration she hears is echoing across the country, as criticism of the U.S. refugee resettlement program grows. It’s fueled in part by the arrival of thousands of articulate Iraqis who often speak English. Many are highly educated, accustomed to a middle-class lifestyle -- but stunned to find themselves unemployed, receiving only brief assistance and facing poverty in America.

The White House has asked a task force to review how America treats its refugees and it is expected to propose short-term fixes and larger reform in coming months.

Some critics say the recession has exposed flaws that already existed. Volunteers from Utah, Texas, Kentucky and elsewhere say they discover refugee families who don’t have enough food or coats or towels. Children in New Jersey have waited months to start school because no one has arranged for immunizations.

“If top government officials who have the authority to change things truly understood the suffering faced by refugees who have already endured so much to seek safety in the United States, they would have increased funding for resettlement substantially by now,” said Jen Smyers, who works in Washington, D.C., on refugee policy issues for Church World Service.

The Obama administration acknowledges that the program may be facing challenges beyond the economy.

“We have received growing numbers of reports about the challenges refugees are facing after arrival in the U.S.,” a White House official said. “This is partly due to the economic downturn, but it also has to do with the fact the U.S. refugee resettlement process, especially on the domestic side, has not been reviewed in many, many years.”

How it works. » The aim of the 1980 Refugee Act is to get refugees working and self-sufficient as quickly as possible.

The federal government provides $900 per refugee to resettlement agencies, such as the International Rescue Committee, to help get refugees established in their first homes.

Agencies can use more than half for administrative costs. But at least $425 must be spent on each refugee -- typically covering rent, utilities, food and furniture. The money can easily disappear in the first month as the agencies try to quickly find refugees jobs.

Though some refugees are highly educated, others can’t read in any language and have no work experience. Their lives have been spent waiting in refugee camps, dependent on international aid. Everything from electricity to washing machines is new and confusing.

The unemployed may briefly receive refugee cash assistance; some turn to welfare.

Answering their every question is an impossible task for caseworkers -- who are often young, inexperienced and paid little to manage dozens of families, critics say.

Caseworkers may share no common language with a family. An interpreter may be paired with a refugee from an opposing ethnic group or tribe. An ethnic Burman and a Karen are from the same country, for example, but speak different languages and have a history of conflict.

“There is a real lack of understanding of context by many resettlement agencies of the people they are serving,” said Veronika Martin, executive director of the Karen American Communities Foundation. “For many Karen, the only experience they have had with a Burman person has been on the other side of a gun.”

‘Immediate measures’ needed. » The federal government focuses on monitoring employment, leaving many questions unanswered about how refugees are faring.

But the new head of the federal Office of Refugee Resettlement, Ethiopian refugee Eskinder Negash, points to the program’s overall achievement: resettling more than 2 million people.

“This is about saving lives,” Negash said. “I’m not saying they’re not struggling, but I’m afraid we can’t just look at it and say the system is abandoning them.”

Shortly after his appointment this summer, he said he had “never met or heard of a refugee going hungry” -- a claim volunteers challenge.

Resettlement agencies also generally defend their work, pointing to refugee success stories and questioning the accuracy of criticism by volunteers. But in June, the International Rescue Committee called for reform.

“Immediate measures must be taken to ensure that Iraqis, as well as all other refugees resettled in America, do not fall victim to homelessness and poverty,” it warned.

The IRC’s report said Iraqis are grateful to be safe, but often filled with anguish about their new life. Many are unable to find work; professionals find their degrees are not recognized in many fields. Families relying on welfare cannot even pay their rent, the IRC said.

The struggling economy has especially hurt refugees, said Charles Shipman, refugee coordinator in Arizona.Typically, 90 percent were self-sufficient within a few months, Shipman said, which meant they didn’t rely on Arizona’s lean benefits for the poor or unemployed.

Now, just 50 to 60 percent of refugees have jobs soon after arrival, he said. With minimal public assistance available, “it’s challenging.”

In Utah, where the economy has been considered resilient, 65 percent of refugees were placed in full- or part-time jobs in fiscal 2008. This fiscal year, 38 percent found work.

Next year, the state will track refugees’ success from housing to education. It is assigning new refugees to caseworkers for two years, instead of a handful of months.

“You have to keep track of folks until they’re well on their way to being able to go it on their own,” said Gerald Brown, the director of the Utah Refugee Services Office. “Dozens and dozens and hundreds of people were falling through the cracks.”

‘Take responsibility.’ » Burmese refugee Andy Paw arrived in Utah about two years ago, after living in a Thai refugee camp for 10 years. He rode the bus two hours to get to his first job at Taco Bell. Most days he didn’t get to take lunch during his shift. He didn’t have enough money to pay his bills.

Frustrated, he called Zan -- who is his aunt -- for advice.

Zan was born under a tree in the rainy season in 1954, when the fighting between the Burmese government and the Karen, her ethnic group, had already begun. “I was a refugee since I was in my mother’s womb,” the small woman says.

Her family eventually fled to Thailand, where she now leads the Karen Women’s Organization, which has more than 40,000 members.

She told her nephew to push for help from resettlement workers, which he says led to a better job at a beef processing plant in Hyrum. Zan urges her distraught callers who speak English to do the same. She sometimes alerts agencies, such as the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, or e-mails resettlement staff in the U.S.

But she has a question for America: “If you don’t want to take responsibility, why did you take this big number?”

Tribune reporter Kristen Moulton contributed to this story.