By Julia Lyon | The Salt Lake Tribune

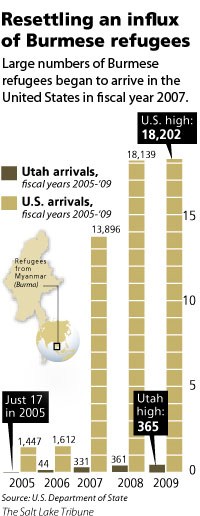

Four years ago, when the U.S. offered impoverished Burmese refugees freedom in America, thousands of them didn’t care.

Despite years of living in primitive camps on the Thai border, they hadn’t given up the dream of going home to Burma, renamed Myanmar by the ruling military junta. Fear and confusion fed by rumors grounded hundreds, if not thousands.

Stories were “as crazy as, you go to America and people will turn you into canned tuna,” said Fern Tilakamonkul, a program officer with the International Rescue Committee in Thailand.

To accurately explain life in America, the U.S. is getting creative in camps, from posting celebrity photos to offering copies of an MTV show.

Since the Mayflower, most immigrants have come to America and not looked back. News of their success or failure traveled slowly, if at all.

But residents of Thailand’s largest refugee camp, Mae La, now so commonly own cell phones that an enterprising resident has opened a repair shop. The phones allow departed refugees to share accomplishment and hardship, and to spread news like the 2008 murder of a 7-year-old refugee in Salt Lake City.

At Mae La refugee camp this fall, word got back about a family thriving in Des Moines

-- but residents also wondered whether it’s true that homeless refugees live under bridges.

Four years after the U.S. opened its doors to mass Burmese resettlement, only about half of those eligible in the camps have applied.

‘A lot of opportunities’ » In photos pinned to a bulletin board at Mae La, a Burmese family is meeting with their caseworker and children are playing at a day care center, all in Salt Lake City.

On another board, an explanation of the different kinds of families in America includes gay parents and features a picture of Tom Cruise, Katie Holmes and their daughter.

In a four-part play, refugee actors portrayed a Karen family trying to decide whether they wanted to go to the U.S. Among the thousands who attended, each generation brought its own perspective; a grandmother’s reluctance to resettle can ground an entire clan.

Newsletters handed out in the camps refute rumors, such as a story about Arnold Schwarzenegger greeting refugees at the Bangkok airport. They answer basic questions such as the cost of rice, and whether people can bring their clothes to America.

One includes advice from a refugee in Indiana. Neineh Plo explained the U.S. social welfare system might not be as generous as other countries, “but there are a lot of opportunities. I want to remind [refugees] that the U.S. is a capitalist country, and the more you can work, the more you will get .”

Sharreh, a refugee in Houston, admitted his parents “honestly, are not happy. But I can tell you they are happy to see their kids have the same opportunities as all other kids, such as going to good schools.”

Copies of an MTV program about a young Burmese refugee’s life in Texas also were given out, to watch on televisions in coffee shops, restaurants or in some homes.

Content to stay. » Hsi Hsa Paw, the 24-year-old school coordinator at Umpiem refugee camp in Thailand, has not been won over. She was born in Burma, but she has no memory of the country.

She feels students in the growing camp need her. Umpiem is bigger now than it was four years ago, when the U.S. began resettling refugees in large numbers. More than 3,000 arrived in 2009 alone, escaping conflict in Myanmar.

“I like the environment, I love the people also,” she said.

In the nearby Thai town of Mae Sot, 62-year-old Chang One also doesn’t want to resettle in America. Thousands of Burmese exiles, essentially illegal immigrants, wait in the town for democracy to return to their homeland.

The physics and English teacher fled to Thailand in 2006 after his friends were arrested, fearing he was next.

Today, he says, his daily life is steeped in bribes and compromises. The former democracy organizer pays a “fee” to the police each month so they don't bother him. Without proper immigration documents, he can’t leave Mae Sot, which is surrounded by Thai checkpoints.

But he feels America is not a paradise, and Asian culture is where he is at home.

Some of the thousands living in camps want to resettle in America, but aren’t eligible to apply through the typical process because they arrived after a 2005 deadline.

Thai officials originally thought the numbers would shrink as resettlement got underway. Instead, those who leave are being replaced by new arrivals.

“Sometimes I feel like I am staying in a cage,” said Aung Hein, 23, who came to Mae La in 2006.

Back from America » Winston Win made it to America -- the former Burmese track champion walked across the Moei River to Thailand in 1990. He had participated in anti-government protests in 1988 that he believed put him in danger.

Win settled in Minnesota as a refugee in 1993. But he returned to the Thai border in 2005, one of a number of refugees who go back hoping to help their people.

In Mae Sot, called “Little Burma” by some, he volunteers in schools for the children of Burmese immigrants, teaching them songs and showing them magic tricks.

On Friday nights, he’s often at a restaurant called Aiya, where aging Burmese activists sing about the decades-long war while throwing back bottles of rum and smoking a brand of cigarettes smuggled in from Myanmar. They sit beneath pictures of Che Guevara and their imprisoned democracy heroine, Aung San Suu Kyi.

At a recent political event, Win, 70, spoke of Winston Churchill, the prime minister who led Britain through the dark years of World War II.

“Winston Churchill was surrounded by this fascist, infamous man, Hitler,” he said as rain pounded down this autumn. “You know what he said?... ‘We will never surrender’ ... This dictatorship [in Myanmar] will perish somehow. We will never surrender.”

Losing faith » Not everyone shares Win’s faith. Moo Thaw, 46, arrived at Mae La as a young man. He imagined he would spend “just a moment” -- a few months or years -- in his new bamboo house before returning home to Burma.

When earlier resettlement opportunities arose, he waited, thinking the turmoil in his home country would improve.

Almost two decades later, he’s seen his daughter marry within the compound. A teacher, principal and Baptist pastor, he has finally lost confidence in his country’s future. “The war is worse,” he said.

He now wants to come to America.