| (insert your NIE or newspaper logo here) |

Weekly Online LessonOnline Lesson ArchiveGrade Level: 6-8

|

Libraries Go Digital

On

Tuesday, December 14, 2004, Google -- the Web's most popular search

engine -- announced it would help five of the world's top libraries

to digitize their books and make them available online for free.

On

Tuesday, December 14, 2004, Google -- the Web's most popular search

engine -- announced it would help five of the world's top libraries

to digitize their books and make them available online for free.

The goal is to convert about 17 million or so books from ink and paper to zeroes and ones, then create a searchable collection of the titles and complete texts.

"Google's mission is to organize the world's information," said Larry Page, Google co-founder, "and we're excited to be working with libraries to help make this mission a reality."

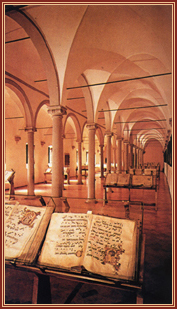

The entire collections at the University of Michigan and Stanford University will be converted, along with a portion of books from Harvard University, New York Public Library, and the Bodleian in Oxford, England.

Google

estimates the project will cost between $150 million and $200 million

and take about a decade to complete.

Google

estimates the project will cost between $150 million and $200 million

and take about a decade to complete.

While this plan is the largest of its kind to date, it certainly isn't alone in its mission. The Library of Congress and a group of international libraries from the United States, Canada, Egypt, China and the Netherlands recently announced their collaboration to convert and post about one million books. They expect to get about 7 percent of the collection online by April 2005.

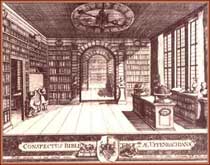

Libraries have long served as vital sources for housing and sharing information, ideas, and ideals. Over 117,000 public libraries operate in the United States, and there are many more thousands worldwide. If the trend to move books online continues, by the end of this century, any Web surfer could browse and retrieve millions of texts with just a few mouse clicks (or verbal commands).

To celebrate onset of this literary revolution, this week you'll uncover how and why books and libraries were created and maintained over the centuries. You'll also get some help figuring out how the Dewey Decimal System works.

Early

Collections

Early

Collections

To get an idea of how and why libraries were first created, let's visit the History of Libraries site in Greece.

You can skip the Introduction, if you'd like, and dive right into Mesopotamian History, beginning with the Sumerians.

After reading the first page, continue through the section, including The earliest libraries of archives, The classification of the tablets, The period of Hamurabi, and The library of Assurbanipal.

In what part of Sumerian community would a library reside? What products of daily life at that time drove the need for libraries? What kinds of insights into their culture do these libraries offer today's researchers?

Next, browse through Egyptian and Prehistoric Aegean histories.

By

what methods did these cultures record and copy their texts? How were

these different from those used by the Sumerians? In what ways, do you

think, did the recording and duplicating of these records contribute

to the development of language and writing, as well as the communication

of ideas and imagination?

By

what methods did these cultures record and copy their texts? How were

these different from those used by the Sumerians? In what ways, do you

think, did the recording and duplicating of these records contribute

to the development of language and writing, as well as the communication

of ideas and imagination?

Now, let's turn our attention to the Hellenic and Roman peoples of the sixth century.

What role did schools, teachers, and students play in the development, use, and appreciation of books and libraries? What were some of the pitfalls of copying texts by hand?

Lastly, at this site, let's peruse the Byzantine, Medieval, and Renaissance periods.

In what ways did books and libraries change during these eras and why?

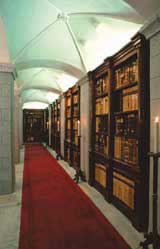

If you have time, you can check out the history behind some of the world's famous Libraries, including the Herzog August in Germany, the National of Austria in Vienna, and the Bodleian at the University of Oxford.

Who were the primary people involved that led to the creation of each library?

Diggin' Dewey

![]() If you've ever visited

a library, you've probably located a book by matching the number you

looked up in the library catalogue with the one imprinted on the book's

spine.

If you've ever visited

a library, you've probably located a book by matching the number you

looked up in the library catalogue with the one imprinted on the book's

spine.

But does this number mean anything, or is it just the way one library chooses to catalogue its collection?

To find out, let's visit a ThinkQuest site that explains the Dewey Decimal System (DDS). Click to Visit Site.

Read the introduction, then click on the page-flipping book at the bottom right to go to the next page for a brief explanation of what is included in a library's DDS.

Next,

Meet

Melvil to read about his contributions to librarianship.

Next,

Meet

Melvil to read about his contributions to librarianship.

Then, run through the Pre-Dew Review, to clarify the difference between fiction and non-fiction, and discover what a call number is and how it relates to books on the shelf. Here, you'll also get the scoop on how the call numbers of fiction and non-fiction books are different.

You might think the site's section titled, Dewey and the Alien, might be a work of fiction, but instead it is way to help you remember how the system works.

Try to memorize the stories. Without looking, can you name the categories in each 100 block? Check the Dewey Chart to see how many you named correctly.

Also review how Book Topics and Websites are catalogued.

For a more detailed look at the DDS, check out the Let's Dew It! pages, then take the Ultimate Challenge.

Check your knowledge with the Quizzes and Puzzles.

In what ways does having this system help librarians, as wells as library visitors? What is the significance of having all libraries follow this system?

Newspaper Activities

Browse issues of Targetnewspaper and look for any stories about your local libraries, or about libraries elsewhere. Maybe someone has donated a large collection of books, or perhaps the library is changing the way visitors can search for a book. How many books does the library hold in its collection? How did the library procure most of its books? Are there any special preservation efforts underway? What information does the library's website provide on its history, location, or collections?

© Copyright 2004

Learners

Online,

Inc.