| (insert your NIE or newspaper logo here) |

Weekly Online LessonOnline Lesson ArchiveGrade Level: 7-12

|

Do Suspected Enemies Have Rights?

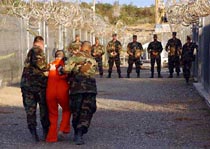

On December 2, 2003, the Pentagon said it would allow a lawyer to meet with suspected "enemy combatant" Yaser Esam Hamdi, a Louisianan of Saudi descent captured in fighting in Afghanistan after 9/11. Hamdi is just one of hundreds "enemy combatants" — American and foreign — suspected as al-Qaeda or Taliban terrorists who are being held by the U.S. military either in the U.S. or in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

On December 2, 2003, the Pentagon said it would allow a lawyer to meet with suspected "enemy combatant" Yaser Esam Hamdi, a Louisianan of Saudi descent captured in fighting in Afghanistan after 9/11. Hamdi is just one of hundreds "enemy combatants" — American and foreign — suspected as al-Qaeda or Taliban terrorists who are being held by the U.S. military either in the U.S. or in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

Although this is the first notable concession by the U.S. government to grant any civil rights to these detainees, the government maintains that they are not required by law to grant these "enemy combatants" any constitutional rights — whether they are American or foreign, detained on American soil or in the Constitution-free zone of Guantanamo Bay (which is on foreign ground that's leased by the U.S government). Such an official stance, in fact, dates back to the political and social upheaval that occurred during and leading up to World War II.

With the onset of World War II, because of their "enemy ancestry," thousands of Japanese Americans were essentially imprisoned by the U.S. government. Either their movements and behaviors were carefully monitored by the government, or they were "evacuated" from their homes and relocated to internment camps. Many evacuees were held for up to four years, with little hope of court trials that could absolve them of suspicion.

This forced movement and ethnic-based discrimination by the government splintered local communities and inflicted hardship and loss on many innocent civilians. It also fueled national and international debates over the civil rights of suspected enemies during times of war.

This forced movement and ethnic-based discrimination by the government splintered local communities and inflicted hardship and loss on many innocent civilians. It also fueled national and international debates over the civil rights of suspected enemies during times of war.

Although the situation of today's war-time detainees is not identical to that experienced by those in the 1940s, they are similar in some ways. So this week, you'll uncover the history of Japanese immigration and citizenship in the U.S. and get insights into how this era's events and sentiments may affect our local, national, and global communities.

The Japanese American Experience

Start your journey at A More Perfect Union: Japanese Americans & the U.S. Constitution, created by the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History.

Start your journey at A More Perfect Union: Japanese Americans & the U.S. Constitution, created by the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History.

Listen to or Read the Introduction with John Chancellor. Then Begin the Story Experience either through the Printable Version or by following along through the Rich-Media Version.

Step into Immigration, and learn about Issei: The First Generation, movements into Hawaii and the U.S. Mainland, and how some people pushed for Legalizing Racism.

Why were so many Japanese drawn to Hawaii and the continental West Coast? How were they treated by other citizens and why? Do you think the bubble-gum cards of 1938 may have indeed influenced society's prejudice in the future, or not? How did descendents of the Issei help legally integrate their ancestry into America's ethnic fabric?

Next, learn about the Removal of Japanese-Americans. Here, you'll discover how Crisis: Pearl Harbor fueled racial conflict, even though the majority of Japanese Americans didn't share Japan's sentiments toward the U.S. and had nothing to do with this attack.

Next, learn about the Removal of Japanese-Americans. Here, you'll discover how Crisis: Pearl Harbor fueled racial conflict, even though the majority of Japanese Americans didn't share Japan's sentiments toward the U.S. and had nothing to do with this attack.

Also read about the Constitution & the Executive Order, the removal Process, Moving Out of homes, and making the First Stop: Assembly Centers.

Why did President Roosevelt sign the Executive Order? How did the order affect families and communities? How would you have felt if you were a Japanese American or had a friend who was? Do you agree that the government had just cause to force the evacuees to give up their homes and lifestyles? Do similar sentiments apply to today's war-time detainees? Why or why not?

When you read about their Internment experience, you'll explore the Permanent Camps and their Conditions. You'll find out how Home=Barracks for the detainees, and how many kept busy with Work, Community Activities, and Arts & Culture.

In what ways do these living conditions compare with those experienced by prisoners of Adolf Hitler's concentration camps? How about with those at Guantanamo Bay? What are the differences and similarities in the political circumstances, daily activities, and types of people held at these places?

In what ways do these living conditions compare with those experienced by prisoners of Adolf Hitler's concentration camps? How about with those at Guantanamo Bay? What are the differences and similarities in the political circumstances, daily activities, and types of people held at these places?

In the Loyalty section, you'll find out what Japanese Americans had to do to assess their allegiance and work through the imposed circumstances. Read about the Questionnaires, Segregation, Expatriation & Repatriation, and The Draft.

Do you think it was fair or appropriate for the government to target the Nisei for this type of assessment and segregation? How did the men react to the draft? What do you think you would have done under those circumstances?

Finish up this series with inspecting their Service efforts and how American society has worked for Justice in the aftermath of the events that occurred.

What were some of the ironies of a Japanese American serving in the U.S. military? How long did it take for the Office of the President to offer a formal apology to its Japanese American citizens? What did all of these events have to do with the U.S. Constitution? How well are Japanese Americans accepted in today's society?

Do you think these historical experiences affect how modern suspected "enemy combatants" are treated or viewed by society? Do you think it affects how other people of similar ethnic ancestry are treated or viewed by society? How much does the press report on the detainees or their circumstances?

Newspaper Activities

In current issues of Targetnewspaper look for stories about "enemy combatants." Does the story describe any related legal, political, or social issues? Do the detainees seem to be allowed any basic civil rights? How can their living conditions be described? How are the detainees being treated? What is the government doing to process and formally arrest or release them? Are any activists protesting the military detention of American or foreign citizens in the U.S. or at Guantanamo Bay? If so, on what grounds are they basing their protests? How is the American government, as well as foreign governments and groups, responding?

© Copyright 2003

Learners Online, Inc.